Documentary Review by Elizabeth Gaikwad

The Musical Brain – Writer/director Christina Pochmursky, producer Vanessa Dylyn, Matter of Fact Media

For me this is one of the most interesting documentaries made about the scientific evidence that music and emotions are fundamentally wired into the brains of human beings. Unlocking these dimensions of the brain through music is an incredibly liberating and enlightening experience. The documentary was initiated by Dr Daniel Levitin, neurologist, musician and an Associate Professor at McGill University, Canada, who is well known for his exploration into the brain and music through his books, ‘This is your Brain on Music’ (see review below) among others. Levitin interviews and conducts experiments with a stellar cast of musicians, Sting, Michael Bublē and Wyclef Jean, to explore the effects of music on the brain and the associated emotions.

This documentary is set on the premise that “Music does not exist outside the brain” Take a moment to think about that… that sound is only registered in the brain when it enters as vibrations into the ear and the brain begins to process and form patterns and associations.

Sting agrees to a number of experiments. The first is where, while in an MRI machine, he just thinks about music, he doesn’t actually hear it, and his brain and body starts to “groove” to imaginary music, thus linking the music directly with dance and movement. The next experiment, Levitin plays many different types of music through headphones while Sting was again in the MRI machine. All music registered in his brain except ‘muzak’. There was zero stimulation of the brain while “elevator” music was played! Conclusions have been drawn that intense memories are entrenched with musical soundtracks – we all recall events where something significant happened…and what song was playing! Neuro-chemical tags are released by the brain, and the old saying applies, “what fires together…wires together”. The more senses that are stimulated, the more memorable the event.

This documentary presents various other experiments, showing amazing connections in the brain -babies who were played music whilst the mother was pregnant recognising the music when played to them at 12 months; patients with Alzheimer’s Disease, remembering word for word the songs wired into the brain from 60 years earlier; experiments with a 4 month old child whose brain reacts to patterns played, and recognises subtle changes in the patterns. All these experiments reveal that as the brain develops, music becomes very much part of how the brain “wires” together.

Daniel Levitin sums up these experiments by saying “The brain is a giant prediction device; it always tries to figure out what will happen next.” Musicians experiment with this idea and accordingly the listener will attempt to order the sound based on their own musical experiences and conditioning.

It is now a well known fact that if you are enjoying the sounds that you are listening to, the brain produces “feel good” hormones called endorphins that convert into sheer pleasure!

Another Neuroscientist, Charles Limb of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, conducted an experiment with jazz keyboardist, David Cain. Whilst David was in a FRMI machine, he was given a keyboard to improvise along with music being played. Dr Limb was able to see the activity in the brain while David was improvising. He discovered that the area of the brain that fired up was the area of self-expression and selflessness, or no inhibitions.

For me, as a Simply Music teacher, I have to say that all these experiments and exploration of the connections of music with the brain reconfirm to me that Simply Music is the perfect vehicle, at any stage of life, to shape the connection of the self with music. Providing students with the tools required to self generate, and express themselves through music are written as the stated goals of Simply Music! So quick…go and practice and enjoy the “feel good” endorphins!

Further information about the documentary

Some videos featuring Daniel Levitin

Ted Talk by another featured researcher Charles Limb on hearing, the brain and beauty

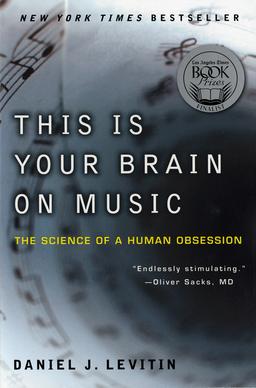

Book Review by Gordon Harvey

This is Your Brain on Music – written by Dr Daniel J Levitin

If a tree falls in a forest and no creature is there to hear it, does it make a sound? The answer is that it creates vibrations in the air, but that the sound only exists after our eardrums have been manipulated by the vibrations and our brain has done a whole lot of work to make those vibrations mean something.

What the brain does to make this meaning occur is the subject of this fascinating and accessible book by Daniel Levitin, who, as a musician and music producer as well as a cognitive psychologist, is ideally placed to tell this story. It turns out that music processing is one of the most complex operations the brain undertakes, engaging multiple regions of both hemispheres. For example, it has been found that rhythm and meter are extracted in different brain regions, melody in yet another. Music involves a far more diverse array of processes than say, language, because it is connected with more varied emotional, physical and intellectual responses.

Levitin begins by giving us a good deal of useful and easy-to-understand background information about music theory, the physics of sound, and the structure of how the brain works in order for us to better understand this journey. To me, it’s fantastically exciting to learn how we instantaneously figure out so much – we can isolate musical content from all the other sounds bombarding us at any time, hear the pitch of each instrument and yet distinguish between different instruments of the same pitch, distinguish tempo and meter, understand the words, interpret the emotional message, form an opinion, remember similar experiences, and even anticipate what will come next, all from discrete regions of the brain working in complete accord. We even unconsciously fill in information that isn’t there, like hearing where a melody will go without the notes being played, or hearing an instrument as if it were in a room of a particular size and construction because an artificial reverberation effect in the recording made us think so.

Our perception of music goes beyond simply interpreting input – we add learned cultural values and personal experience into the process, and use these to anticipate and weigh the music we hear against what we expect. Our ability to anticipate things – from danger to a punchline – is a big part of how we’ve acquired the skills we have today. Our brains are highly adapted to anticipation, and we are very good at applying our frames of reference to what to expect, and be entertained by having those expectations either fulfilled or violated – a dance between familiarity and novelty.

Levitin provides lots of examples of this in a variety of music (conveniently sampled on his website), which provides a great chance to train ourselves to hear and use these perceptual tricks. The famous adagio cantabile from Beethoven’s “Pathetique” Sonata is one of my all-time favorite melodies – now, at least in part, I know why.

What’s interesting for me is to see if this research might tell us more about where music comes from. Why does music exist at all? Are we made or adapted for music, or is music a side-effect of how our brain works? There are various schools of thought among scientists, but Levitin makes a compelling case for important adaptive purposes for music, including roles in attracting mates, developing social cohesion, and promoting generational skills like speech.

There’s still a long way to go, but slowly we are moving towards complete understanding of the way our brain works, what’s going on when we feel an emotion, and how music triggers particular emotions. Like when I reviewed Why Music Moves Us, I wonder if the appeal of music will be diminished when we understand how we’re manipulated by it. Will the magic fade? I don’t think it will for me, and maybe my enhanced understanding will enrich the experience. Perhaps it will aid composers in touching us more deeply or help individuals express their individuality more clearly. This book does an admirable job of explaining what we know so far, while acknowledging that there’s still a great deal of mystery to our relationship with this most human of art forms.