This new occasional series is already contradicting itself in the first edition by discussing not a song but a full-length orchestral piece. Still, the 100th anniversary of one of the milestone events in music is worth commemorating.

This new occasional series is already contradicting itself in the first edition by discussing not a song but a full-length orchestral piece. Still, the 100th anniversary of one of the milestone events in music is worth commemorating.

There are few if any genuinely unprecedented new musical innovations. You can usually trace some kind of ancestry for even the most radical new styles, but Stravinsky’s iconic The Rite of Spring comes as close as any to being truly groundbreaking. Much of 20th century classical music, and perhaps even some music in genres like jazz and rock would probably be completely different without the profound impact of this work. Composed for the 1913 season of Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes and choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky, it certainly had an impact at its premiere, where riots are said to have broken out amongst affronted patrons – although it must be said that the dance performance was perhaps even more scandalous.

The other thing about revolutionary musical developments, like in other art forms, is that they often appear as a reaction to what has gone before, and at a time that in some way feels ripe for change, like when punk burst onto the scene and kicked aside the flamboyance of disco and the indulgence of progressive rock. Europe in 1913 was dominated artistically by the impressionist movement, which seemed not to reflect the great turmoil happening in politics at the time, the eve of the first world war and the Russian revolution.

So what was it about The Rite of Spring that made it so confronting and so different to the classical music that came before? The answer – if it can be reduced to one word word – is rhythm. Although almost all music has rhythm, most classical composers never exploited rhythm as a way of making a physical impact in the way Stravinsky did in this piece. I’m not saying classical composers were not sophisticated in their use of rhythm, but nothing else used rhythm so massively – sometimes using the entire orchestra to pound out jagged, pulsing patterns of dark dissonant chords, eschewing sophisticated melody yet fabulously, richly orchestrated.

So what was it about The Rite of Spring that made it so confronting and so different to the classical music that came before? The answer – if it can be reduced to one word word – is rhythm. Although almost all music has rhythm, most classical composers never exploited rhythm as a way of making a physical impact in the way Stravinsky did in this piece. I’m not saying classical composers were not sophisticated in their use of rhythm, but nothing else used rhythm so massively – sometimes using the entire orchestra to pound out jagged, pulsing patterns of dark dissonant chords, eschewing sophisticated melody yet fabulously, richly orchestrated.

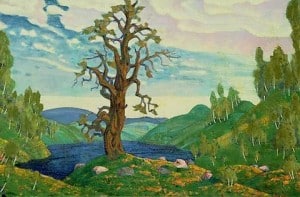

The melodies, such as they were, were drawn mostly from folk sources, and presented in snippets, just enough to draw you in to the dark heart beneath the surface. Listen to the very beginning, where a haunting call is played eerily high on bassoon, only to be dragged down into a tangle of discordant lines, escape momentarily but to be swallowed by a monstrous, irresistible riff thundered out on strings and horns. For me, it brings to mind the idea that our idyllic image of nature – the flowers and blue skies beloved of the Impressionists – are a gauzy veil obscuring the violence and tumult of nature. And real or not, I have found nothing in music that renders so vividly and viscerally the dark side of the natural world and the primitive side of our own human nature. But fear not! Music safely touches things in us that nothing else can. Listen closely to a good performance of The Rite of Spring on a good sound system, or better still, at a good concert hall, and I think you will emerge in some small way a different person – maybe even a better one.