Jerry Jeff Walker, who passed away recently at the age of 78, is remembered as one of the artists who brought country music out of the backwoods and into the mainstream. He was very prolific but he will always be remembered for one song: Mr Bojangles, written in 1968 but covered countless times since then by artists as varied as Sammy Davis Jr, Garth Brooks and Robbie Williams.

What is it about this song that makes it so widely appealing? For one thing, like so many great country songs, it tells a story. It’s a real story of a man Walker met while in jail for public intoxication. The homeless man (no relation to the entertainer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson), used the name to conceal his identity from police. They and others in their cell were talking, but the mood darkened when Bojangles spoke about the death of his dog, so to cheer things up, he danced. Like all good stories, this one had a mixture of happiness and sadness, reflected perfectly in the song’s jaunty waltz rhythm and the memorable chords in the verses, with their moody descending bass and uplifting return to the top.

The Chords:

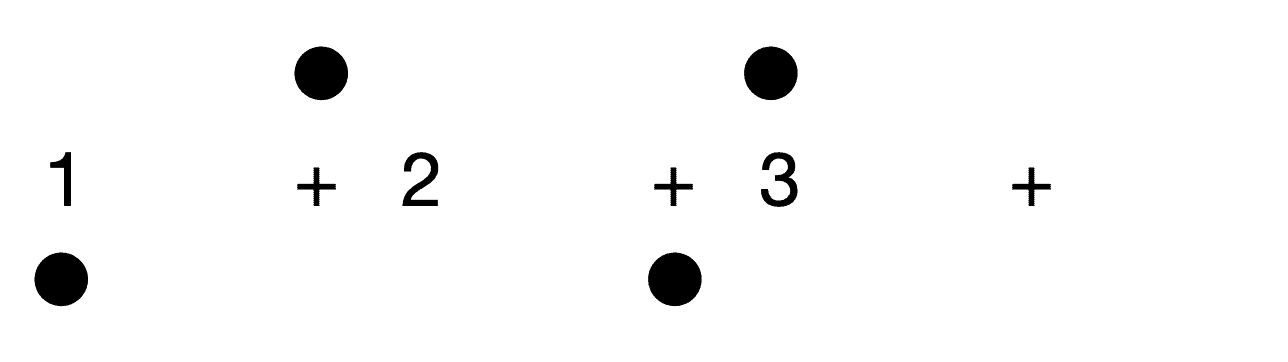

So let’s have a look at those verse chords. As the bass descends, the chord itself stays the same, creating gentle tensions relieved by the final F and G chords. It’s a well-used device that’s been employed by everyone from JS Bach to NW Moore, but in this song, the brisk rhythm seems to offset the wistful harmonies. The progression is worth learning just because it makes a great foundation to build your own song from. Play around with the ratio, the tempo, the breakup of the chords, and it can be turned into almost anything. It’s one of those situations where something looks more complicated on paper than it really is. If you look at a version, it will probably look something like:

That’s the way the chords are properly represented, but I’m sure it’s not how Jerry thought of them. For him, the first four chords were simply a C chord on top while the bottom note (ie LH on the piano) travels down the white keys from C to G. Then he finished off with a simple F and G to get us back to the beginning. Play each chord with a 1:3 ratio and you’ve got the rhythm.

In fact it’s so simple, I think we could complicate it a little for the sake of a smoother sound: instead of playing the usual C chord, bring its G down an octave so you’re playing the notes (from bottom to top) G, C and E. Remember you’ll stay on this chord while the LH goes down through the C>B>A>G pattern. For the F, pivot your RH up. That is, keep the C in place and move the other two notes up one white key so you’re playing notes A, C and F. That’s a more convenient way of playing the F chord. Then when it’s time for the G chord, just move the whole lot up one to the next white keys and there’s your G. Then maybe you could dial up the rhythmic interest by using a variation on the ratio. If you’ve started the Accompaniment Variations with your Simply Music teacher, you can use any of the 1:3 variations or come up with your own (including, if you’re using it to invent your own song, changing the ratio entirely). Here’s one you could use to make it a little jazzier:

Cover versions

Here’s a playlist sampling the amazing array of cover versions of the song. If you don’t have time, I recommend going straight to the Nina Simone version. It’s my favourite, although as someone whose middle name is Maudlin, I’m bound to favour a version that taps into the song’s poignant side.