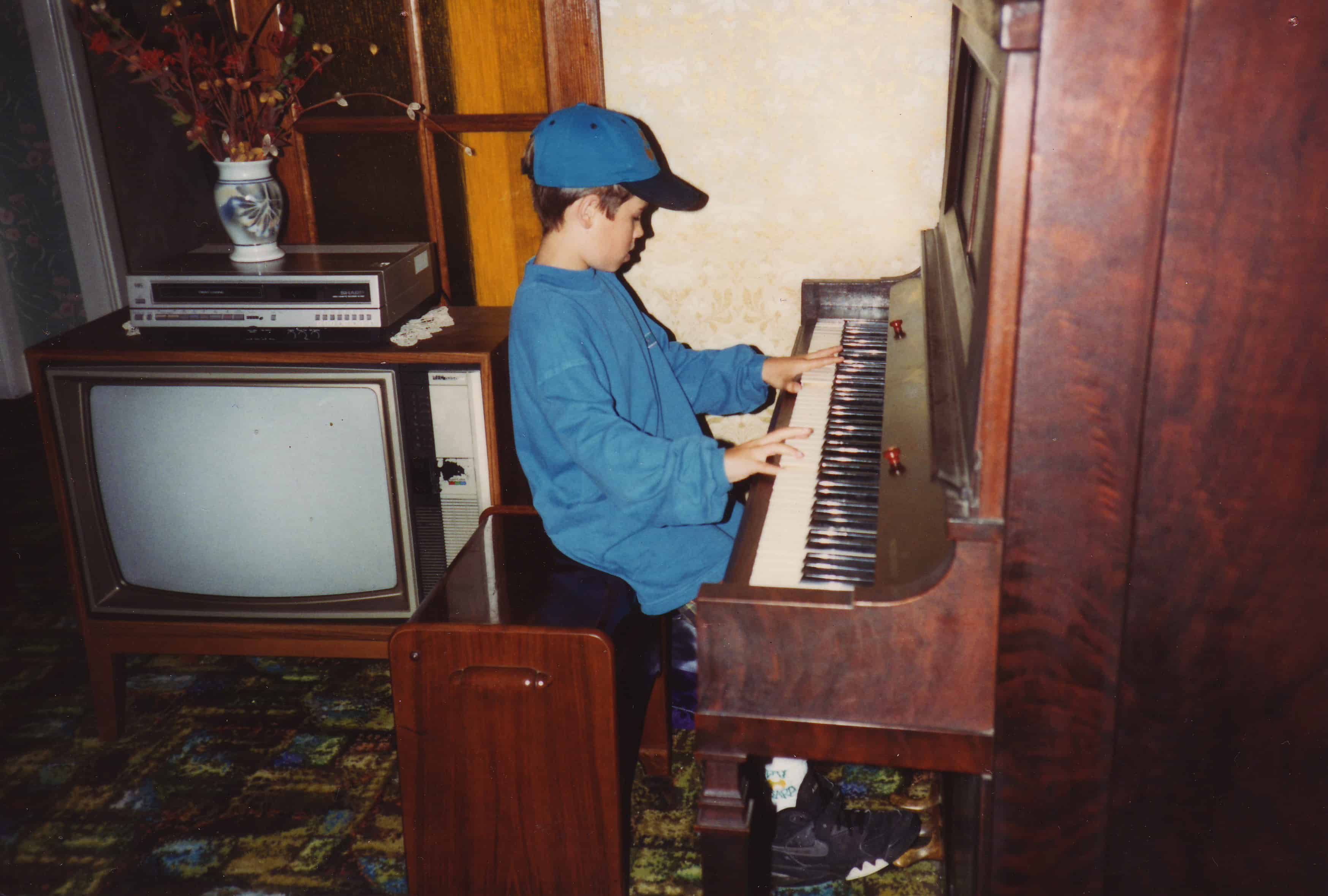

I can recall countless fond memories of growing up in a household that was filled with music. I would get home from school and my dad, who was a music educator, would have anywhere from one to ten students in our home. At that time, he was teaching a method called “Music Logic”. This was a new approach that taught students how to read music using “intervals” – the distance between one note and another. Clearly, this approach offered great value, however, it was still a traditional method, in that it was still based on students learning how to firstly read music as a means of learning how to play. Students learnt a mixture of standard classical, blues and contemporary pieces, as well as many of my dad’s original compositions. These compositions would become the foundation of what we now know today as Simply Music.

When I was a baby, Dad would place me on top of his piano and play for me for hours on end, composing many of the original compositions that now weave their way throughout the Simply Music curriculum. Songs like “The Mirron,” “If You Call,” “Deep River” and others, were songs that became physically etched and ingrained into my memory, note by note, from their very inception. The music that filled our home, perhaps not typical of the average Australian household, was a combination of jazz, funk, R&B, classical, as well as my dad’s original compositions.

The names Oscar Peterson, Quincy Jones, Whitney Houston and Beethoven are just a few of many that come to mind when I think of those who helped mold my own musicality and deep love for music. Clearly, I would include my dad’s name in that list. At the same time, I also recall listening to my fair share of “obligatory Australian-listening” – John Farnham, Kylie Minogue, INXS, AC/DC and Men at Work.

In the afternoons and evenings, I would sit outside of our living room where lessons were held and not only listen to people playing music, but to people learning music, note by note, for hours. I literally mean hours. This experience clearly contributed to music becoming what I now consider a lifelong companion. It has given me such a confidence, respect and affinity with the power of music and what it truly can do for people.

I remember hearing students having their breakthrough moments in music, where somehow my dad was able to articulate an approach that left people feeling connected to their musicality and being empowered by it. I remember hearing the sound of joy that would wash over people as they were experiencing the “ah-ha” moment of embodying their musicality, where they may have previously thought they were one of those people who “weren’t musical,” but were now playing excerpts from “Moonlight Sonata” or playing great-sounding jazz-style ballads and blues pieces, or accompanying a piece they would then bring back to their churches or homes, and bring communities and families together. It was powerful, and it was something that I experienced vicariously through hundreds upon hundreds of students.

By default of who my father is and what he stands for (that everyone is naturally and profoundly musical), I have always come from the school of thought that music was something anyone and everyone could do. I never once experienced music as being something that you would “learn later” once you acquired a skill for reading. Music was just part of it all. The ability that Dad had to see music in a different light, as “shapes, patterns” etc., and to then be able to translate that idea to other people, is quite incredible. However, for me, it was just the norm. I knew of nothing else, really; that was just how it was for me. The confidence that this built for me, without me even knowing it at the time, has been something I am still deeply grateful for.

When Dad was growing up, he and his three older brothers were all required to take piano lessons as part of their extracurricular activities. This is where Simply Music truly began. My dad says that he was about three years old when he first began to hear music, and “see it,” in his mind’s eye, as two-and three-dimensional shapes and patterns. When he began music lessons, at the age of seven, his teacher would play the songs he was learning, and my dad would hear the songs and see those same shapes and patterns across the instrument. He actually never learned how to read music, he would just watch the teacher’s hands and start to dissect the piece, in his mind, as a series of “patterns, shapes, and sentences.” It was his means of access to music. It was a type of musical “synesthesia,” – a blending of the senses. The teacher totally knew that Dad was not reading the music at all, and although my dad seemed to think he had his teacher fooled, he most certainly did not. The teacher said to my grandmother, “Neil isn’t reading the music at all; he’s faking it.” Luckily, this is where one tiny instance has now shaped the musical self-expressions and lives of tens of thousands of people around the world. If my Grandma had been stern about it and said to my dad, “Reading music is how music needs to be learned. Listen to your teacher, Neil, you need to learn how to do what he says,” then we really wouldn’t have Simply Music at all. We would all still be stuck in a world where so few students actually learn how to play, where learning by reading music was the access to it. But thankfully, my Grandma said something along the lines of, “Well, he might not be reading music, but so what, listen to how well he is playing.” So the teacher continued the lessons, leaving my dad to do his own thing – continuing to figure out different ways of dissecting the music internally into shapes and patterns, and therefore laying a foundation for what has now emerged as Simply Music.

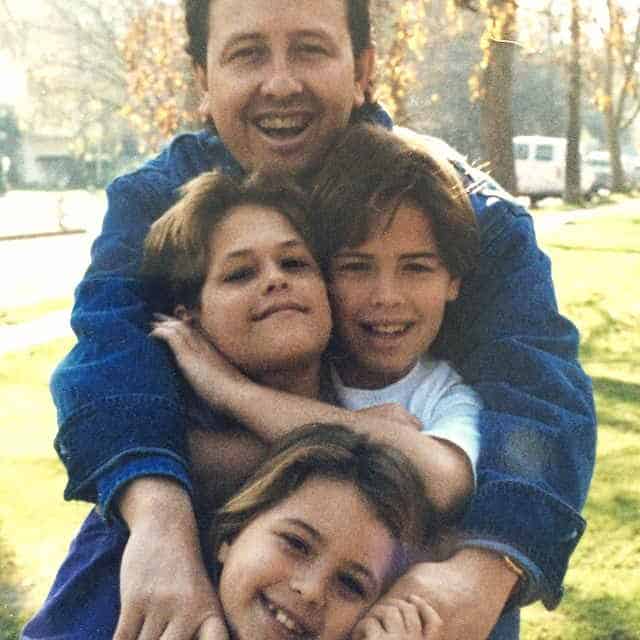

This all really came full circle in the early 1990s, when we moved as a family to the United States.

I remember quite well the moment when my parents told us we were moving to America. My brother, sister, and I were completely against it. What ten-year-old would want to leave his family and friends to go into the unknown of a brand new country?

Dad has always dreamed big and always envisioned having not merely an ordinary life, but an extraordinary life. In Australia, for the most part, the city where people are born is where they spend their entire lives. Since most of the country is a desert, we are all pretty much forced to live in a few coastal areas. Living in Sydney versus Melbourne, for example, isn’t as stark of a difference as living in Sacramento versus Texas or New York City. Typically in the U.S, people will go to college or to work for a company that is based in a completely different state from where they were born. As such, they relocate their immediate families, and that is just the norm. Families and communities in Australia are often together for the duration of their lives. So for my parents to move us all to the other side of the world and start there with no family was something that wasn’t too well received by some, but this was a collective decision that my Mum and Dad made, and it was clearly fueled by a calling that Dad had to follow. His vision was that he would transform the face of the earth musically, and America is a much better vehicle to do so on an international level.

So, in September of 1994, we were on a plane to what I thought of as a frightening new chapter of our lives, into the abyss, to start fresh in Sacramento with all of our life possessions in three suitcases. The Visa we had, gave us temporary access to the country, but no assurance of our ability to remain here and build a life. That would be something that my father would have to earn – it was a long, complex and costly process. Twenty-three years later, my family are all dual citizens here and we wouldn’t trade it for anything.

For a brief period of time my Dad continued to teach the reading-based Music Logic program, and quickly built a thriving studio. Naturally, he also established a reputation as being a great teacher.

Chalk It Up! Festival.

One day he was presented with a unique challenge (which was to become a defining moment). He received a call from a government agency looking for piano lessons for an eight-year-old boy who was blind. The agency was somehow involved with funding a new type of surgery that they thought could restore his sight. My dad wasn’t exactly sure of how they had heard about him but when they called and asked if he could teach the boy how to play, he said “yes.” Given that Wade was without sight, and given my dad’s thinking at the time, teaching the traditional approach to reading music would be out of the question. It was in that moment that a thought suddenly occurred to my dad. Looking back on his own experience of learning music he thought to himself, “I never learned to read when I was young, why don’t I see if I can teach him to play in a similar manner to how I taught myself as a boy. I bet I could show him how to physically feel on the instrument, the shapes and patterns that I see in my mind’s eye.”

My dad decided that his then-current approach of teaching students how to read music as a means of learning how to play would be entirely inappropriate for this boy. Instead, my dad’s approach would be all about the pure, playing-based concept. It was a natural reconnect to Dad’s own experience of learning music as a child that he would tap into to teach Wade. The results were astonishing. Not only was Wade learning quickly in this approach, he was going home and teaching these ballads, classical, blues, and accompaniment pieces to his four year-old sister, and she was also blind.

After this caught on, the word started spreading. What was once a ‘one-man show’, Simply Music had a demand that couldn’t be met with just Dad at the helm. This experience led to the creation of an entirely new way of thinking about music, of looking at music and of teaching music. This was where the Teacher Training Program began, and the growth of Simply Music was well underway.

Dad wanted to transition existing students into this new approach that he decided would be what everyone would now experience – a complete playing-based approach to music – and it was staggering how positive of an experience everyone was having across the board.

All walks of life seemed to just connect with this natural “tapping in” to their own innate natural musical ability, demystifying on a large scale those who not only believed, but were convinced that they weren’t musical. People young and old, with learning differences, physical disabilities, past musical experience or no experience at all, were experiencing piano lessons as music, not technique or reading-based approaches.

A really sad story but with a great turnaround was one where an older student of Dad’s had a series of “tattoo-like” dots on the side of her hand. As a child in lessons, her piano teacher would sharpen a pencil and, whenever she made a mistake, would poke the side of her hands with the sharpened pencil. The piercings left a permanent reminder of the punishment she received. It was basically a tattooed daily reminder of how she was “un-musical,” but it was completely turned around by my dad proving otherwise. As far as I’m concerned, that is the definition of a breakthrough.

These are gifts that are inspirational and life-changing, and something that Dad has made possible in this world for not only myself, but also for people who have had a lifetime of thinking otherwise, or as their first exposure to music: a positive, creative, and expressive one.

Dad never forced lessons upon any of us as kids, yet he empowered all of us with an experience that would shape our confidence to express ourselves in whatever way seemed natural for us. My brother, sister, and myself all have an incredible ear for music as a result.

On my twelfth birthday, Dad gave me a present that would forever change my life and put me on my own unique musical path. He gave me what to this day remains one of my all time favorite albums, and arguably one of the best jazz albums of all time: Miles Davis’s “Kind of Blue”.

I had previously played the baritone horn in middle school, but now I wanted to play the trumpet. This album just spoke to me. The simplistic beauty of Miles Davis’s playing, his sparseness and melodic phrasing and “storytelling,” was all very reminiscent in some way of Dad’s playing (or Dad’s of his playing). The beauty of Miles was really in the space between the notes: what he wasn’t playing almost had more beauty than the flurry of notes that John Coltrane would play as counterpart. It reminded me of Dad’s ability to convey such sensibility, sensitivity, and emotion in playing so few notes and using the spaces in between to shape an expressive story.

Voodoo Daddy at the House of Blues in Las Vegas.

Over time, I advanced on the trumpet and in my musicianship, and it became central to my life – playing in my school bands, jazz band, orchestra, marching band, drum and bugle corps, and going on to form a funk/rock/jazz/latin band called ¡Búcho! I also played in both the American River College Jazz Band and in the California State University of Sacramento’s jazz band (and didn’t even attend the school!). Yet, I always kept these roots of simplistic, sensible and sensitive storytelling near and dear to my heart, especially while learning to improvise. As was the case with my dad, I, too, never really connected well with the reading of notes as a means to being able to play, but thankfully I developed a very strong ear for pitch and rhythm due to all of those hours outside of so many other people’s lessons, listening intently, and compounded by the times that Dad would show me how to play fairly advanced pieces with such an easy approachability.

In hindsight, many of the approaches I took to learning how to play the trumpet were in their way my own version of Simply Music. I also totally faked reading for a long time, but always found my own ways to figure things out with patterns and shapes. I love the fact that Dad never forced any of us to take lessons, but just allowed our musical abilities to come into fruition, since we were constantly surrounded by and enveloped with music. Had I not had this history of musical exposure, I wouldn’t be able to hear and play like I do.

I remember when I was about seven or eight, Dad told me that I could make up my own song just by putting together three or four notes. At first, I was very reluctant to comprehend this, and I thought that I wouldn’t be able to because of all the beautiful songs he had made – surely that took skills I didn’t feel I had at the time. He completely proved me wrong. I hesitantly sat down at the piano and outlined the notes of a basic “C chord” from bottom to top, and then walked down a note. He sat beside me, processed those four notes, and within thirty seconds, we had the foundation for the song that he would name “Beautiful Boy,” a beautiful ballad that is taught in the Simply Music curriculum. These approaches are one of the core foundations for many layers of Simply Music.

The ability to break free from the shackles of our own minds and to just let music be a language as much – if not more than – language as a language is an important tool that we all possess. It just takes the right guidance to “dis-cover” an approach where the core tenet of it all is that as humans, we are all absolutely, naturally, and profoundly musical, without exception.

We all improvise on a daily basis, yet most of us are unaware of this fact. When we have conversations, we technically have never had the same conversation twice, unless it is a scripted dialogue. Even then, our inflections or delivery of these conversations will always differ ever so slightly. We pull together words from the vocabulary we have built up over the years and combine them in a new order or sequence every time we speak. When we improvise in music, the exact same thing is happening on a neurological level. During improvisation, a part of our brain called the lateral prefrontal cortex (the area of self-monitoring, self-reflection, and introspection) shuts off and leaves us more willing to make mistakes and be creative. This is basically us in our purest, most organic form of being. Many other parts of our brain light up that increase our autobiographical nature and self-expression. This same activity does not occur in the brain when we are simply reading a dialogue. These are all incredibly beneficial things for the brain on a neurological level and on an emotional level as well. This was something that I unknowingly learned the value of at a very young age: that music is more of a language than language is in itself, and it benefits the brain in so many ways. None of the science behind it was ever a focus for me; it was just naturally there as a tool of my self-expression, and I got to reap all of the neurological and musical benefits!

I started teaching Simply Music at the age of nineteen and loved it because I had this inherently deep connection to the curriculum that no one else really had. It gave me the ability to pass on some of the incredible tools and insights that I had learned throughout my own musical upbringing. The fact that music can come so naturally to us all is something that every human being deserves: to have music at least as a companion – if not a passion or profession – for our entire lives.

Simply Music is something that is truly special. As a witness to how many lives have been impacted as a result of one kid’s struggle to learn how to read with the desire to be creative and expressive, I know that I speak for a lot of you when I say this: from the bottom of my heart, Dad, thank you. Thank you for giving me and thousands of people around the world the best gift anyone could ever give, a lifelong love and companion that I can’t wait to start sharing with my own two sons for their lives: the gift of music.

Do you have a story about how Simply Music was introduced to you or impacted your life? Reach out to us or share it below.