Oliver Sacks is a neurologist and author known for his books exploring the strange and remarkable world of people with brain damage. In the 1960’s he published Awakenings, a study of his work with post-encephalitic patients who, after decades of immobility and non-communication, could be suddenly and temporarily ‘awakened’ into lucidity by the drug L-dopa. The book was later made into a famous film. Another of Sacks’ works, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, was also made into a fascinating film, an opera adapted from the real story of a patient who was incapable of recognising anything or organising the simplest task until he discovered he could sing perfectly well, and could go about his daily tasks if he sang them.

Oliver Sacks is a neurologist and author known for his books exploring the strange and remarkable world of people with brain damage. In the 1960’s he published Awakenings, a study of his work with post-encephalitic patients who, after decades of immobility and non-communication, could be suddenly and temporarily ‘awakened’ into lucidity by the drug L-dopa. The book was later made into a famous film. Another of Sacks’ works, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, was also made into a fascinating film, an opera adapted from the real story of a patient who was incapable of recognising anything or organising the simplest task until he discovered he could sing perfectly well, and could go about his daily tasks if he sang them.

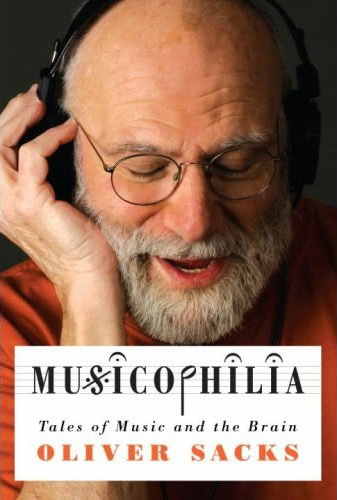

Musicophilia is all about music and its relation to brain function, and is full of amazing stories of music’s ability to transform the lives of people with serious psychiatric illness, such as Clive, an amnesiac with a memory for any experience of literally a few seconds, and yet who can play, read, conduct, improvise and remember enormous amounts of music. How is this possible? Sacks speculates that musical memory is different to other forms of memory, because experiencing music happens entirely in the present. For many people like Clive, music is a cornerstone of life and the only way they can feel fully alive.

Sacks, a musician and music lover himself, draws a distinction between music and other forms of communication, and notes music’s ability to touch parts of the brain (and the heart) in ways nothing else can. Even language, while very closely related to music, appears to originate from a different part of the brain, although the brain is a wonderfully flexible thing, and when parts used for one skill are damaged, others can adapt and begin to take over their role. Interestingly, though, Sacks points out that although it’s crucial that basic language skills are learned from infancy, musical skills can be learned at almost any age.

Sacks points out that music is something unique to humans, and something that plays a unique role in people’s lives. We can recreate musical memories and experiences spontaneously in our heads that are almost as rich as actually listening and playing, and can reappear decades after the original experience, long after other memories have gone. Somehow something about music has a more direct connection with the brain. Perhaps, like dreams, music, with its more abstract way of addressing emotions, is a safe way of experiencing feelings. He reminds us that music, while causing us to feel emotions like grief more deeply, provides solace at the same time. There are stories in the book of people who are for various reasons unable to express emotion of any kind, until they sing and are, like the L-dopa patients, awakened into full self-expression. It’s only during those times that they and the rest of the world can connect with each other.

The endlessly inspiring stories in this book cover the extremes of musical experience, from musical seizures, synaesthesia and hypermusicality to the wonderful contribution of music therapy. Although in the end the book probably tells us more about the brain than about music, I ended it clearer than ever that to be human is to be profoundly musical, and that a life without music is a life that isn’t fully self-expressed.

Musicophilia is published in by Alfred A Knopf (USA) and Picador (Australia)