Story of a Song – Summertime

Found in: Story of a Song

A lot of music unites people. Occasionally it divides people. With its contentious depiction of racial stereotypes, the opera Porgy and Bess seems to have experienced the ebb and flow of acceptance over the years, but even its cultural detractors will recognise it as one of the most important musical works of the 20th century.

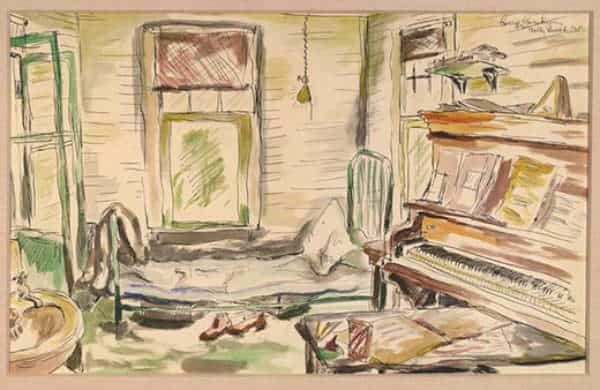

The story behind the opera begins in 1926, when the popular songwriter George Gershwin read the novel Porgy by DuBose Heyward. He immediately wrote to Heyward with the idea of writing an opera, but it wasn’t until 1933 that Gershwin, his lyricist brother Ira and Heyward finally began their collaboration. The work was radical in various ways: Gershwin wanted to create an opera in the European tradition, but to borrow from African-American blues, jazz and spirituals, as well as from the life and language of black people in South Carolina. Beyond that, he insisted that the first production feature an entirely black cast, a bridge-building gesture that launched several brilliant operatic careers.

That said, the first production was not a huge success, and it wasn’t until after Gershwin’s death in 1937 at age 38 that Porgy and Bess grew in importance, succeeding on Broadway as well as becoming accepted as serious opera and becoming the source of several of the most famous tunes in popular music.

Of all those tunes, the most popular and enduring is Summertime. It is one of the most covered songs of all time, with more than 25,000 known recordings by artists of every kind. While it has a distinctive style in its original form, something about it makes it endlessly adaptable. Gershwin wanted to create something in the style of a spiritual, and to most commentators he succeeded way beyond his initial brief. He uses it four times in the opera, including as a lullaby at the very opening.

Here’s the very first recording by Abbie Mitchell including Gershwin himself on piano.

What is it about this song that makes it so special and so timeless? Of course, it’s in the nature of music that our response will always be very personal, but there must be some fundamentals about the way the song is constructed that make it so universally appealing. It has a kind of ambiguity that allows us to find our own message. To some, it evokes lazy sunny days, to others it has a brooding or yearning quality. The chords have a way of playing with our expectations and anticipations. Looking at a popular song sheet version, it starts on a dark, tense Am6 chord and moves to an E7, a chord that is commonly used to lead us to some kind of change or resolution, but here just falls back to the Am6, rocking us between the two, lulling us into a hazy torpor that feels relaxed but still seems to anticipate something. A B in the bass under the E chord emphasises the gentle sway. “Fish are jumping” offers some uplift, but soon it settles back into the Am6 & E7. The real change comes at “hush little baby” with C Major, a chord which works as the light to Am’s shade. The effect is like a sudden fresh breeze on a balmy afternoon. The string fills (usually included in song sheets) wrap around the melody, adding a flowing feel with bluesy passing half-steps.

You could teach yourself an accompaniment pretty easily using the above mentioned song sheet. If you know how to work out inversions, you’ll maximise the effect by keeping the voicings close. For example, if you play the Am6 chord in root position (A, C, E, F#), the E7 will work well by pivoting up around the E to play B, D, E and G#. Play it slow with a 1:1 ratio and that lazy feel will emerge. Adding the melodic fills between the sung phrases makes it very authentic.

Porgy and Bess came at a time when America was beginning to assert its own serious art forms, and in his composition, the New York Jewish Gershwin looked to southern black culture for the opportunity to develop a unique new musical hybrid. Summertime, along with so many others of Gershwin’s unforgettable songs, tilled this fertile soil and has given rise to countless wonderful musical flowerings, feeding back into jazz, blues, pop, Broadway and so much more.

Here is a small selection that demonstrates the song’s versatility:

- Billie Holiday gives it the New Orleans treatment.

- Kat Edmonson seems to bring Billie Holiday into the modern world and cleverly segues into another classic, Feelin’ Good.

- For another great segue, check out Mahalia Jackson’s powerful gospel singing seamlessly blending the song with Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child

- Jimmy Ricks and the Ravens deliver a very swinging R&B harmony version.

- Miles Davis elevated the musical into high art in another arena with Gil Evans’ jazz reinterpretation of Porgy and Bess.

- Legendary saxophonist John Coltrane turned it into a typically uncompromising modern jazz workout.

- Harmonica virtuoso Larry Adler (who played with Gershwin in his youth) brought in Peter Gabriel for a tender, respectful rendition.

- Angelique Kidjo cleverly shines a modern African light on the song.

- Doc Watson delivers a bluegrass interpretation.

- It was recorded by R.E.M for their most dedicated fans.

- Morcheeba give it a chill out groove.

- Rita Reys pushes and pulls the melody in all kinds of fun ways.